Demystifying English Pronounciation

I’d like to talk about my recent enlightenment regarding the English accent. One mystery I used to have was how American English (AE) differs from British English (BE). AE sounds smoother and more natural, while BE seems a bit rigid and serious. My own English speaking also carries an accent. I tend to articulate every syllable and try to say the whole sentence in one go, if possible. That actually makes it harder for native speakers to understand me. Books related to pronunciation helped me understand why.

If you’re encountering the same issues, these short notes may be worth reading.

Elements of Pronunciation introduces five common patterns: weak forms, consonant clusters, linking, contractions, and stress-timing. While the book sheds light on various pronunciation changes, I found that it mostly lists the rules without explaining why these patterns exist. Without understanding the reasons behind them, and with the rules being somewhat vague, I found it difficult to move forward.

By contrast, American Accent Training by Ann Cook explores the causes and offers specific exercises for every phonetic point.

In a nutshell, AE intonation is like an orchestra. Each syllable is a musical note. Some words are stressed and thus have a higher pitch. Pitch moves like walking down a staircase. Some syllables are reduced, and vowels often turn into schwa sounds. Intonation, word connections, and the TH sound are the areas I’m focusing on most—and I’ve listed my notes on these topics below.

Intonation¶

Vowels take two staircases to stress.

- A short vowel + unvoiced consonants

- A long vowel + voiced consonants

Three ways to stress a word: volume, lengthen the word, and pitch changes.

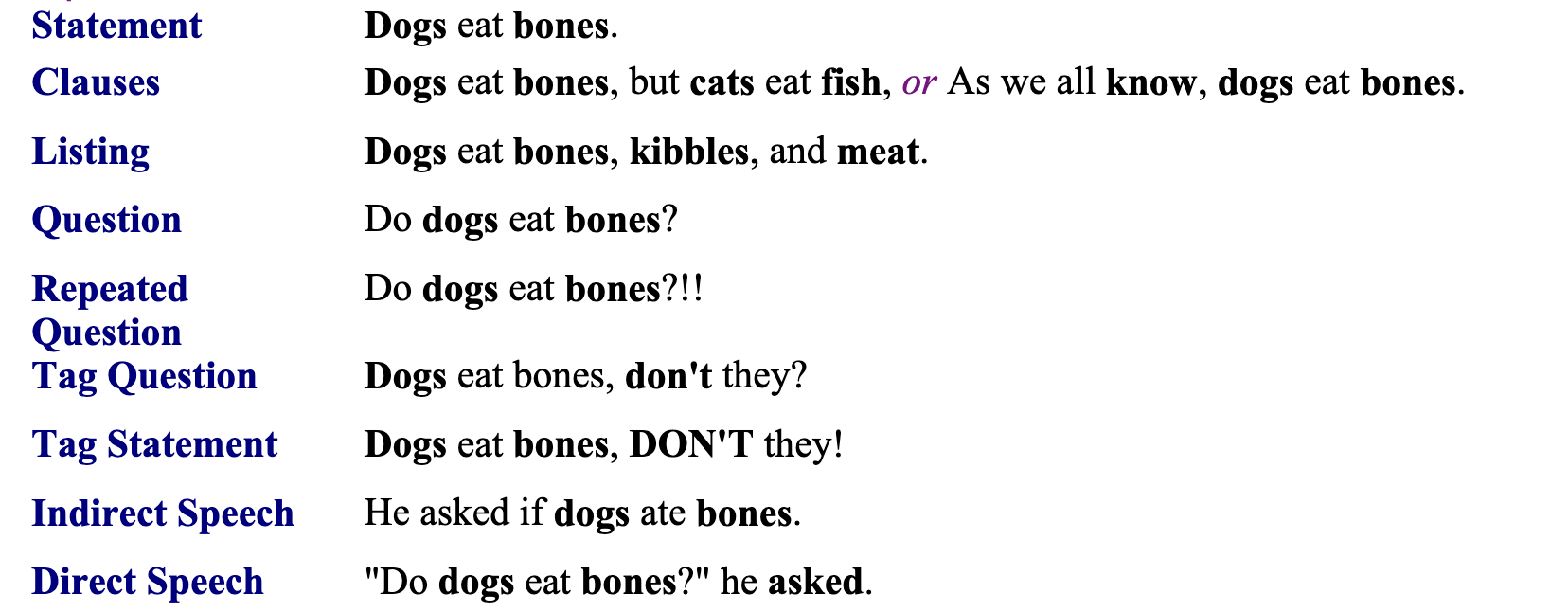

Staircase intonation: when and where to stree

- introduce a new noun

- replace pronouns, stress verbs

- statement, question, emotional/retorical statements

Reasons to stress:

- new information

- opionion

- contrast

- can’t, no need to stress other negative forms like shouldn’t, couldn’t.

New sentences don’t have to start new staircases; they can continue from the previous sentence until you come to a stressed word

Spelling and numbers:

There is a distinct stress and rhythm pattern to both spelling and numbers—usually in groups of three or four letters or numbers, with the stress falling on the last member of the group.

Acronyms and initials are usually stressed on the last letter.

Squeezed-out syllables:

Intonation can also completely get rid of certain entire syllables. Some longer words that are stressed on the first syllable squeeze weak syllables right out.

Syllable stress:

One syllable = one musical note. Words that end in a vowel or a voiced consonant will be longer than ones ending in an unvoiced consonant

Complex intonation: word count intonation patterns: adj., n., adv.

- compound noun stress patterns: In noun pharases, each individual word was represented by a single musical note.

- Descriptive phrases (adj. + n., adj. + adv.): the stress always fall on the noun. Nouns are new information. In the absence of a noun, stress the adjective.

- It’s short.

- It’s a short story.

- It’s really short.

- Set pharases: word images; indicators of a determined use.

- two-word descriptive pharases -> set pharases, emphasis shifts from the second word to the first.

- painkiller, a love letter, passersby

- Nationalities: depends on the importance of a word

- an American guy: guy can be left out without changing the meaning.

- an American restaurant, descriptive pharases

- American food: food is a weak word

- an American teacher, descriptive pharases

- an English teacher, subject, set pharases

Grammar:

The verb tenses are thrown down in the valleys. Articles and verb tense changes are usually not stressed.

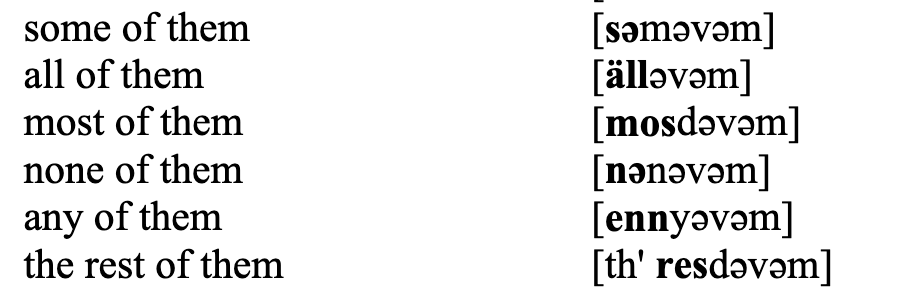

The th of them is frequently dropped (as is the h in the other object pronouns, him, her)

Supporting words: (CD 2, 8,10-11)

Can or Can’t:

- Can, /k 'n/, stress the verb -> positive

- Can’t, /kæn (t)/, make it short and stress can’t + verb -> negative

- can do -> extra positive

- can’t do -> extra negative

Build an intonation sentence

The miracle technique:

Learn to hear again. A child can hear every sound of every langue while adults stop listening for the sounds that they never hear.

Word groups and phrasing

Breath groups and idea groups.

Reduced sound¶

The position of a syllable is more important than spelling in pronunciation.

photograph, photography

Syllables on a peak or a staircase (intonation) are strong sounds.

Syllables that fall in the valleys or on a lower stairstep are weak sounds, thus reduced.

Reduced sounds are valleys.

Reduce a vowel by tonning done or changing to a schwa.

Fix overpronouncing: You skim over words; you dash through certain sounds.

Articles are very reduced sounds.

- the, a: schwa sounds. For example,

a nugly hat, an orange ->a nornj,thee(y) easy way

In the beginning, you should make extra-high peaks and long, deep valleys. When you are not sure, reduce.

Reduced sounds: when a sound is reduced, the following sound is usually stressed. (Ex. 1-52, CD 2, Track 26)

- To

- preposition: reduced to /t/ or /tə/.

- To school; to the store; He went to work; To be or not to be.

- to + (consonant) + vowels: becomes /d/ or /də/.

- He told me to help. She told you to get it. At a quarter to two.

- preposition: reduced to /t/ or /tə/.

- At

- small grunt + reduced /'t/ or /ət/.

- We’re at home. I’ll see you at lunch.

- at + vowels: becomes /'d/ or /əd/

- Dinner’s at five.

- small grunt + reduced /'t/ or /ət/.

- It

- It and at sound the same in context /'t/

- Turn to /'d/ or /əd/ between vowels or voiced consonants

- For: reduced to /fr/. Unless it is at the end of a sentence /for/

- From: /frm/. At the end: /frəm/

- In: reduced to /'n/

- An: reduced to /ə’n/

- And: reduced to /n/ or /ə’n/

- Or: /'r/

- Are: /'r/

- Your: /y’r/

- One: /w’n/

- The: /th/ or /ə/

- A: /ə/

- Of: /'v/ or /ə/

-

- Can: /k’n/

- Had: /'d/

- If there are two hads, reduce the first one.

- Jack had had enough. [jæk’d hæd’ n’f]

- Had you ever had one?

- If there are two hads, reduce the first one.

- Would: /wud/

- Was: /w’z/

- What: /w’t/, /w’/, /w’d/

- Some: /s’m/, /səm/

- That

- the relative pronoun and conjunction are reducible to /the 'd/ or /th’t/

- demonstrative pronoun cannot be reduced: /æ/. That book.

- Her, his: /h/ is reduced -> /er/, /is/

Plurals:

- /s/, ends in a voiceless consonant: cups

- /z/, ends in a voiced sound or a vowel sound: keys

- /iz/, ends in s, z, sh, ch, x or ge: buses, watches

- /θs/, ends in /θ/: baths, paths

- ðz, ends in th whose sounds changes from /θ/ to /ð/ in the plural: mounth, truth

Word connections¶

liaisons

semivowels: W, Y, R

Vowels don’t touch any point in the mounth but consonants do.

Words are connected in four main situations:

-

Consonant / Vowel:

- when the consonant is /n/, /m/, /l/, /w/ it will be pronounced in liaisions.

- fall off: /fä läff/

- Also used in spelling and number connections.

- when the consonant is /n/, /m/, /l/, /w/ it will be pronounced in liaisions.

-

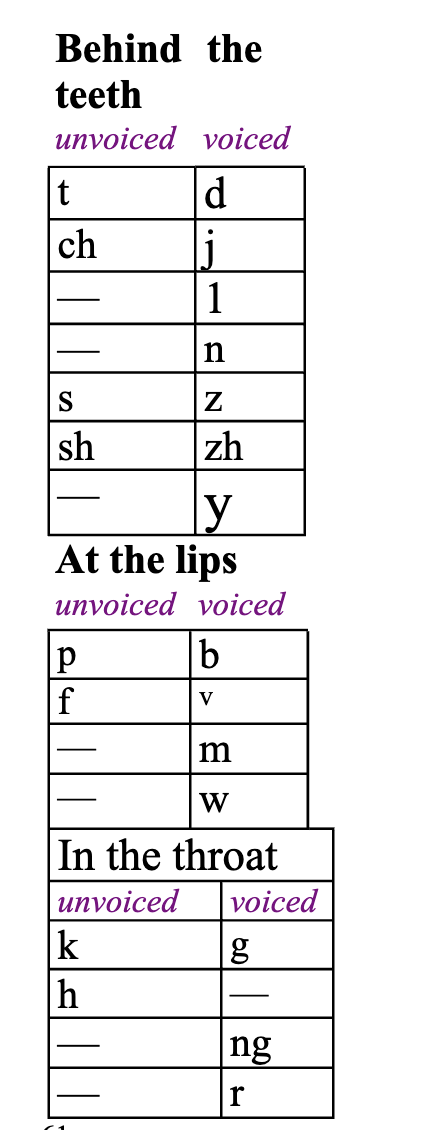

Consonant / Consonant: the next C is in a similar position in the month to the first C. If the first C is /t/, it can be omited usually.

Three general locations of sounds are the lips, behind the teeth, or in the throat. The similar position denotes to the two C’s are in the same location. Such words can be linked togother.

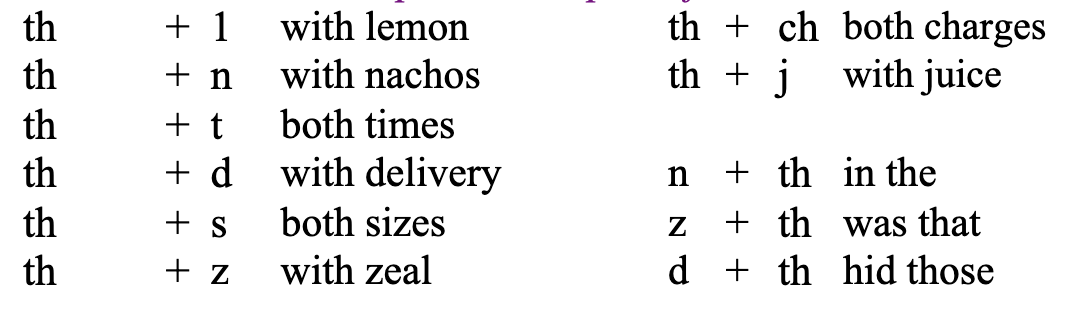

The TH sound is floater between areas. Combinations of various letters forms a new composite sound. (2-9, CD 2, 42)

-

Vowel / Vowel: two Vs are connected with a glide in between which is either a slight /y/ or /w/ sound.

- Go away. /w/

- I also xxx. /y/. Don’t force this sound too much.

-

T, D, S, or Z + Y

Th-¶

Pronounciation:

- Think of a snake’s tongue: a quick and sharp little movement

- Keep your tongue’s tip very tense: darts out (0.5 cm) and snaps back very quickly

- Remind tougue’s position is placed between the teeth or even pressed behind the teeth.

Readings: American Accent Training

Chap 1: Intonation

Chap 2: Word connection

chap 7: Th-sound